The Jihad oF Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio and Its Impact Beyond The Sokoto Caliphate

By Dr. Usman Bugaje

Background

“Oh send on my behalf to my tribe a letter,

To which men or honest women may pay attention,

To their scholar, or seeker after knowledge, desiring

To make manifest the religion of God, giving good advice therein.

I say to him: Rise up, and call to religion with a call

Which the common people shall answer, or the great lords;

And do not fear, in making manifest the religion of Muhammad

The words of one who hates, whom fools imitate.

And do not fear to be accused of lying; nor the disavowal of the apostate;

Nor the mockery of the ignorant man gone astray

While the truth is as the morning;

Nor the backbiting of a slanderer; nor the rancour of one who bears a grudge,

Who is helped by one who relies upon (evil) customs.

None can destroy what the hands of God has built.

None can overthrow the order of God if it comes.”

Shaykh Abdullahi, the younger Brother of Usman Dan Fodio, and the conscience of the Sokoto Jihad, may not have meant it, but the verses he composed above, succinctly summarise their endeavour from start to finish. It all started with a group of young scholars who were rightly worried about the level of ignorance as well as injustices in their society. Their immediate objective was to disseminate the knowledge of the religion clearly and widely. They were motivated by the consciousness of their responsibility and sustained by their strong belief that God was on their side. They faced an array of obstacles, starting from their peers who thought that they were crazy to contemplate a change in the rotten society they were born into, then their contemporary scholars who were eager to find faults in what they did and called them all sorts of names, and ultimately the rulers of Hausaland who realised that the success of this movement was going to be at the expense of their cherished thrones. These obstacles, formidable as some of them were, did not, however, dissuade them from their path. Those movements that were to follow, invariably took similar path. It was a well trodden path, the path of the prophets of old.

This Jihad in Hausaland was what pulled the Hausaland from out of the abyss of corruption, decadence and insecurity, into which the Hausa states had sunk. It gave these states the security and stability which had eluded it for the best part of two centuries and restored to Islam its position of honour and respect. The Jihad also triggered series of similar Jihad Movements in the 19th century Bilad al- Sudan and beyond. These Jihad Movements were to salvage the societies of the region from decay and collapse and radically transformed their polities putting them once again on the path of Islam. This paper is not about the Sokoto Jihad as such, for this has been adequately addressed by other papers of the conference, rather, the paper is about its impact beyond the Sokoto Caliphate. It may still be necessary, however, to begin with some broad outline of the Sokoto Jihad, highlighting those aspects especially significant to its impact beyond the immediate theatre of the Jihad.

It was the good fortune of Hausaland and ultimately of the people Bilad al-Sudan (the land of the Blacks) that Allah raised among their ranks a scholar who was not prepared to accept the decadent status-quo with the usual fatalism, as the will of God, but saw it as his primary responsibility to change it. To be sure, Shehu Usman did not, and could not have, set out early in his life to organise a jihad and to establish an Islamic state and society. In fact little did he realise that his modest effort will lead to any event beyond his little state of Gobir. Even when he ventured out of Gobir to the neighbouring states, partly to source scholars and pursue his higher learning and partly to expand his enlightenment of the wider society, he clearly did not envisage much coming out of his efforts. But from 1774, at the young age of twenty, Shaykh Usman spent about two decades as an itinerant scholar, constantly moving from one place to the other teaching, writing and gathering an increasing following as his fame spread well beyond Hausaland. By the time he settled down at Degel, in the Hausa state of Gobir, about 1793, he found himself at the head of an expanding network of scholars and students, many of whom never met him in person, covering such areas as Masina and Segu in the West and Borno and Chad in the East, sharing his ideas of reform and yearning for change. This then is the movement, the Jama’a, as Shehu called his following, which in course of some three decades slowly but perceptibly eroded the old and corrupt order in Hausaland and having fought and won the Jihad, reordered their society and polities along Islamic lines.

By the end of the first decade, while a young man of about thirty years of age, Shehu’s name had become household in Hausaland. He had emerged at the head of a group of young scholars, yearning for change and sharing some revolutionary ideas. This naturally attracted for the Shaykh, the envy and wrath of the more established scholars. Some of these scholars took him up on a number of issues, especially some of the shaykh’s liberal ideas about women education and role in society and Shehu’s departure from the hair-splitting issues of ilm al-kalam and the dry as dust fiqh to the more relevant issues of understanding the basics of Islam and the elimination of Bid’ah (superstitions), corruption and injustices rampant in the society. The attack on the Shaykh was sometimes done in letters, poems and often in the form of insinuations. In most cases the Shaykh responded by writing, composing a poem or writing whole works. In this process alone the Shaykh wrote more than fifty works, as reported by his son and helper Muhammad Bello.

By the half of the second decade, Shehu Usman had emerged victorious in this intellectual debate that raged for nearly a decade. The intellectual leadership of Hausaland was gradually, if grudgingly, conceded to him. This leadership was in a way formalised in 1789 when Bawa Jan Gwarzo, the powerful king of Gobir, invited all scholars at the celebration of Eid al-Kabir, and showered them with gifts. Shehu was reported to have been given the lions share, in clear recognition of his leadership position. Not surprisingly, however, Shehu declined to accept the wealth showered on him and instead requested the king to grant him five wishes: the reduction of taxes, release of prisoners, freedom to preach, suspension of harassment by state officials especially in respect of women who wear proper Islamic outfit and same in respect of men who adore the turban as a mark of the new consciousness. By this singular act, unprecedented in his time, Shehu Usman earned himself a higher station yet. For the rejection of the gift earned him respect of the king, independence from the establishment and more profoundly endeared him not only to his followers but the ordinary people at large whose interest he identified with and stuck out his neck to protect.

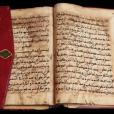

By 1793, when Shehu saw the need to and eventually settled down at Degel, he saw how this small village swelled with scholars and students from all over the Bilad al-Sudan, and transform into a university town. By this time and in the course of nearly two decades of itinerant life, Shehu found it necessary to write a number of books delineating the basics of Islam, such as Kitab Usul al-Din, Kitab Ulum al-Muamalat, Ihya’ al-Sunnah, etc. Many of these books spread far and wide and became the standard texts of study in the growing number of schools and the expanding circles of students all over Hausaland and beyond. Thus while in Degel, Shehu had cause to concentrate on higher studies and found time specifically to attend to and groom women scholars. It was also here in Degel that he found the time to focus on the spiritual training of both his person and the community, often taking time off to go into khalwa. It was significant that Shehu found time for spiritual training only after he thought he had taken care of the basic and more fundamental aspects of Islam. And that even when he started he made sure he did not overemphasise it nor did he regiment the whole community to the Qadiriyya order, which he chose. In Degel Shehu found himself at the head of a large and ever expanding movement of scholars and students which required co-ordination.

If Shehu was oblivious of the potentials of his growing Jama’a, the Hausa rulers were certainly not. For Shehu, the growth of the Jama’a may only mean an end to the ignorance that propelled him into action in the first place and a hope for a more enlightened and therefore peaceful Muslim community. But for the Hausa rulers, every growth of the Jama’a represent a shrink of their power base and more seriously it represents a threat to the tyrannical and corrupt status-quo, where the rulers did as they pleased. Not surprisingly, the first salvo was therefore fired by the increasingly insecure ruling class whose constituency was shrinking and coming to extinction. This was precisely what started the jihad, a clash which was ultimately inevitable.

As early as 1797 or so, following the rise to power of a new king in Gobir, Napata, in 1796, the Jama’a started to face organised state persecution, in the form of physical attack, arrests and imprisonment. Having sensed danger, Shehu started to prepare the community for a confrontation that turned out to be inevitable. He composed a poem which was auspiciously in praise of Shaykh Abdulqadir al-Jaylani, in which he urged the community to acquire arms as it was Sunnah to do so. The tension continued to heighten and Yunfa who took over from Napata as the king of Gobir in 1803 only made matters worse. This prompted the Shehu to compose another work aptly titled Masa’il al-Muhimma in which he argued the necessity for hijra and the need to rise against a tyrannical ruler, but only when the community has the strength to do so. The mood of the community had changed and the Jama’a grew restive. Following a few skirmishes and a threat for an all-out attack on the community from Yunfa, Shehu called for a hijra to Gudu, a place on the boarders of Gobir. He wrote and circulated in the same year yet another document, this time titled, Wathiqat Ahl al-Sudan wa man Sha’ Allah min al-Ikhwan, arguing for the necessity for jihad and urging the Jama’a to come out for hijra and jihad.

The hijra itself started in February of 1804, and before the Jama’a could finish assembling at Gudu, they came under attack, first by Yunfa and consequently by other kings of other Hausa states, and the jihad began. Until April of 1806 when the Jama’a captured Kebbi, they had no base and had to be constantly on the move, carrying their families as well as their libraries, often pursued by their enemies. Yet in the thick of this no doubt tormenting confusion and daunting obstacles, Shehu and his brother Abdullahi still found time to write. In fact, it was in November 1806, at Kebbi, Shehu Completed one of the most voluminous of his works, the Bayan Wujub al-Hijra ala al-Ibad, a work of 63 short chapters that expounds on, not only the necessity of hijra and jihad, but the rules that govern them and how to set up and Islamic administration in the event of victory. Many battles were fought and by 1810, the jihad was in the main over. The Jama’a emerged victorious and found themselves at the head of an extensive area made up of several Hausa states and soon set about the task of reordering this vast polity, the Sokoto Caliphate.

For similar or related articles on this site click the links below:

Alhamdulillah, this is fantastic research, Jazakumullahu khaerah

LikeLike

Please can u continue to sending me update and links of historic and islamic books, novels poems etc?

LikeLike

As we muslim concern we need more books in order to understant and teach other peoples in muslim student society (m.s.s.n) god help us to more books.

LikeLike

Allahu Akbar, may there souls continue to be resting in perfect,marvellous peace amen.

LikeLike

Allah Akbar, I appreciate the advantages of this fortune.May Almighty Allah save their soul in JANNATUL FIRDAUSIII. Ameen. because the most important historical phaenomina in the history of mankind especially in west Africa was that of Shayk Usman Dan Fodio.

LikeLike

thank people send complete history of danfodio

LikeLike

This is great! May Allah reward you abundantly. Ameen

LikeLike

Hamdulillah I have learnt a lot and will further disseminate it

LikeLike